Write yout own fuzzer for NetBSD kernel! Fuzzing Filesystem

How Fuzzing works? The dummy Fuzzer.

Recently I started working on Fuzzing Filesystems on NetBSD using AFL. In the previous post I explained the basics of the fuzzing and the way how kernel can expose coverage data. This post is divided to the 3 sections:

- Porting AFL kernel mode to work with NetBSD.

- Running kernel fuzzing benchmark.

- Example howto fuzzing particular Filesystem.

AFL Port for Net BSD

AFL is well known fuzzer for user space programs and libraries, but with some changes make it works for fuzzing the kernel binary itself.

As a first step to fuzz the NetBSD kernel via AFL I needed to modify it to use coverage data provided by kernel instead of compiled instrumentations.

My initial plan was to replace the coverage data gathered via afl-as with provided by kcov(4). In such a scenario, AFL would just run wrapper and see the real coverage from the kernel.

I saw also previous work done by Oracle in this area where instead of running wrapper as binary, the wrapper code was included in custom library (.so object).

Both approaches have some pros and cons, one thing that convinced me to use a solution based on the shared library with initialization code was potential easier integration with remote fork server. AFL have some constraints in the way how to manage fuzzed binary and keeping it on remote VM is less portable than a situation where we fuzz using a shared library and do not introduce changes to original binary fuzzing.

Porting AFL kernel fuzzing mode to be compatible with NetBSD kernel mainly relay on the way how the operating system manage the coverage data, and can be found currently on github.

Writing own kernel fuzzing benchmark.

Performance is one of the key factors of the fuzzing. If performance of the fuzzing process is not good enough is likely that entire solution won’t be usefull in practice. In this section we will evaluate our fuzzer with practice benchmark.

One exercise that I want to perform to check the AFL kernel fuzzing in practice is similar to password cracking benchmark. High level idea is that fuzzer based on coverage should be much smarter than bruteforce or random generation.

To do that we can write a simple program that will take a text input and compare it with some hardcoded value. If values match Fuzzer cracked the password otherwise will be performing another iteration with modified input.

Instead of password cracker I called my kernel program lottery dev, is a character device that takes an input and compare with the string.

The chances to find one 6 bytes combination (or lucky bytes combination thus to the name) are similar to won the big loterry: every bytes contain 8 bits, thus we have 2**(8*6) => 281474976710656 combinations.

The coverage based fuzzer should be able to do that much quicker in less iterations, as will see feedback from code instrumentations instead of blindly guessing.

I performed a similar test using a simple C program: the program read stdio and compare it with the hardcoded pattern. If the pattern matches program panic if not returns zero. Such test took an AFL about a few hours on my local laptop to break the challenge (some important details can make it faster). The curious reader that wants to learn some basic of AFL should also try to do run similar test on his machine.

I run the fuzzer on my lottery dev for several days and after almost the week it was still not able to find the combination. So something was fundamentally not right.

The kernel module with wrapper code can be found here.

Measuring Coverage for particular function

In the previous article, I mentioned that the NetBSD kernel seems to be ‘more verbose’ in terms of coverage reporting.

I run my lottery dev wrapper code (the code that writes given input to the char device) to check the coverage data using standard kcov(4) without AFL module. My idea was to check the ratio between entries of my code that I wanted to track and other kernel functions that can be considered as noise from other subsystems. Such operations are caused due to the executed in same process context services as Memory Management, File Systems or Power Management.

To my surprise, there was a lot of data but I cannot find any of functions from lottery dev… I quickly noticed that the amount of addresses is equal to the size of kcov(4) buffer, so maybe my data didn’t fit to the buffer inside kernel space?

I changed the size of the coverage buffer to make it significantly larger and recompiled the kernel, with this change I rerun the test. Now when buffer was large enough I collected data and printed top 20 entries with a number of occurrences, for reference there were 30578 entries in total.

1544 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:847

1536 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:869

1536 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:890

1536 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:880

1536 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:858

1281 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/arch/amd64/compile/obj/GENERIC/./machine/cpu.h:70

1281 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/arch/amd64/compile/obj/GENERIC/./machine/cpu.h:71

478 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/kern/kern_mutex.c:840

456 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/arch/x86/x86/pmap.c:3046

438 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/kern/kern_mutex.c:837

438 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/kern/kern_mutex.c:835

398 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/kern/kern_mutex.c:838

383 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:186

308 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/lib/libkern/../../../common/lib/libc/gen/rb.c:129

307 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/lib/libkern/../../../common/lib/libc/gen/rb.c:130

307 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:178

307 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:1568

231 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/lib/libkern/../../../common/lib/libc/gen/rb.c:135

230 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/uvm/uvm_page.c:1567

228 /usr/netbsd/src/sys/kern/kern_synch.c:416

That should not be a surprise that coverage data does not help much our AFL with fuzzing while most of the information that the fuzzer see is related to UVM page management and machine-dependent code.

I decided to remove instrumentation from this most common functions to notice the difference. Using an attribute no_instrument_function should tell the compiler to not put instrumentation for coverage tracing inside these functions.

Unfortunately after recompiling the kernel the most common functions did not disappear from the list. As I figured out the support in GCC 7 may not be fully in place.

GCC 8 for help

To solve this issue, I decided to work on reusing GCC 8 for building the NetBSD kernel. After fixing basic build warnings, I got my basic kernel working. This still needs more work to get kcov(4) fully functional. Hopefully, in the next report, I will be able to share these results.

Fuzzing Filesystem

Given what we already know, we can run Filesystem fuzzing. As a target I choosed FFS as it is a default FS that is delivered with NetBSD.

The reader may ask the question: why would you run coverage based fuzzer if the data is not 100% accurate?

So here is a trick: usually is recomended for coverage based fuzzers to leave them input format, as genetic algorithms can do pretty good job here.

There is great post on Michal Zalewski Blog that describe this process based on JPEG format: “Pulling JPEGs out of thin air”.

But what will AFL does if we will provide already proper inpput format? We know already how the valid FS image should looks like, or we can simply just generate one. As it turns out AFL will start performing operations on the input in similar way as mutation fuzzers does, another great source that explains this process can be found here: “Binary fuzzing strategies: what works, what doesn’t”

Writing mount wrapper

As we discussed in the previous paragraph to Fuzz the kernel itself we need some code to run operations inside the kernel, we will call it a wrapper as it wraps operations of every cycle of fuzzing.

The first step to write a wrapper for AFL is to describe it in a sequence of operations. Bash type of scripting is usually good enough to do that.

We need to have an input that would be modified by fuzzer, and be able to mount it. NetBSD comes with vnd(4) that allows exposing regular file as a block device.

Now the simplest sequence can be described as:

# Expose file from tmpfs as block device

vndconfig vnd0 /tmp/rand.tmp

# Create new FS image on blk dev that we created

newfs /dev/vnd0

# Mount our fresh FS

mount /dev/vnd0 /mnt

# Check if FS works fine?

echo "FFS mounted!" > /mnt/test

# Undo mount

umount /mnt

# Last undo step

vndconfig -u vnd0

From bash to C and system calls

At this point, the reader probably figured out that written in shell script won’t be the best idea for fuzzer usage. We need to change it to the C code and use proper syscall/libc interfaces.

vndconfig is using the opendisk(3) combined with vnd_ioctl.

mount(2) is a simple system call which can operate directly after file is added to vnd(4)

The conceptual code for mounting FS

// Structure required by mount()

struct ufs_args ufs_args;

// VNConfigure step

rv = run_config(VND_CONFIG, dev, fpath);

if (rv)

printf("VND_CONFIG failed: rv: %d\n", rv);

// Mount FS

if (mount(FS_TYPE, fs_name, mntflags, &ufs_args, 8) == -1) {

printf("Mount failed: %s", strerror(errno));

} else {

// Here FS is mounted

// We can perform any other operations on it

// Umount FS

if (unmount(fs_name, 0) == -1) printf("#: Umount failed!\n");

}

// VNC-unconfigure

rv = run_config(VND_UNCONFIG, dev, fpath);

if (rv) {

printf("VND_UNCONFIG failed: rv: %d\n", rv);

}

The complete code can be viewed here

Ready to fuzz FFS! aka Running FS Fuzzing with predifined corpus

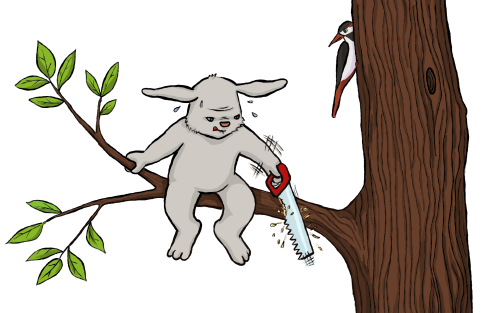

The first thing that we need to is to have a wrapper to provide mount/umount functionality. In the previous section, we already show how that can be done. For now, also fuzzing that we will perform will be doing the same kernel that we run. Isn’t it dangerous? Saw off the branch we are sitting on? Of course, it is! In this exercise I want to illustrate an idea from a technical perspective thus the curious reader would be able to understand better and do any modification by its own. The take away from this exercise is that fuzzing target is the kernel itself, the same binary that is running the fuzzing process.

Let’s come back to the wrapper code, we already discussed how it works.

Now we need to compile it as shared library, this is not obvious but should be easy to understand after we already brought this Sawing Off methafor.

To compile the so object:

gcc -fPIC -lutil -g -shared ./wrapper_mount.c -o wrapper_mount.so

Now we need to create input corpus, as first try we will use large enough binary zeroed file.

dd if=/dev/zero of=./in/test1 bs=10k count=8

And finally run: (the @@ tells AFL to pyut here the name of input file that will be used for fuzzing)

./afl-fuzz -k -i ./in -o ./out -- /mypath/wrapper_mount.so @@

Now as we described earlier, we needs a properly created FS image, to allow AFL perform mutation on it. The difference is the only additional NEWFS(8) command

# We need a block, big enough to fit FS image but not too big

dd if=/dev/zero of=./in/test1 bs=10k count=8

# A block is already inside fuzzer ./in

vndconfig vnd0 ./in/test1

# Create new FFS filesystem

newfs /dev/vnd0

vndconfig -u vnd0

Now we are ready for another run!

./afl-fuzz -k -i ./in -o ./out -- /mypath/wrapper_mount.so @@

american fuzzy lop 2.35b (wrapper_mount.so)

┌─ process timing ─────────────────────────────────────┬─ overall results ─────┐

│ run time : 0 days, 0 hrs, 0 min, 17 sec │ cycles done : 0 │

│ last new path : none seen yet │ total paths : 1 │

│ last uniq crash : none seen yet │ uniq crashes : 0 │

│ last uniq hang : none seen yet │ uniq hangs : 0 │

├─ cycle progress ────────────────────┬─ map coverage ─┴───────────────────────┤

│ now processing : 0 (0.00%) │ map density : 17.28% / 17.31% │

│ paths timed out : 0 (0.00%) │ count coverage : 3.53 bits/tuple │

├─ stage progress ────────────────────┼─ findings in depth ────────────────────┤

│ now trying : trim 512/512 │ favored paths : 1 (100.00%) │

│ stage execs : 15/160 (9.38%) │ new edges on : 1 (100.00%) │

│ total execs : 202 │ total crashes : 0 (0 unique) │

│ exec speed : 47.74/sec (slow!) │ total hangs : 0 (0 unique) │

├─ fuzzing strategy yields ───────────┴───────────────┬─ path geometry ────────┤

│ bit flips : 0/0, 0/0, 0/0 │ levels : 1 │

│ byte flips : 0/0, 0/0, 0/0 │ pending : 1 │

│ arithmetics : 0/0, 0/0, 0/0 │ pend fav : 1 │

│ known ints : 0/0, 0/0, 0/0 │ own finds : 0 │

│ dictionary : 0/0, 0/0, 0/0 │ imported : n/a │

│ havoc : 0/0, 0/0 │ stability : 23.66% │

│ trim : n/a, n/a ├────────────────────────┘

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘ [cpu: 0%]