Digging into Linux FileSystems

UNIX Filesystem story goes back to the first implementation of the operating system. Since then, many different implementations and improvements were made. Due to that FileSystems became quite composed but also rock solid piece of software. Currently, most people treat FS as a black box or an indivisible part of OS. In this article, I will present basics structures and differences between Linux filesystems. This article is an extension to the talk that I gave at DLUG (Dublin Linux Users Group) meetup as a 15-minute speech. Here I will try to summarize everything as a short article. If you are interested in slides from meetup you can find them here

Why you should care about Filesystem?

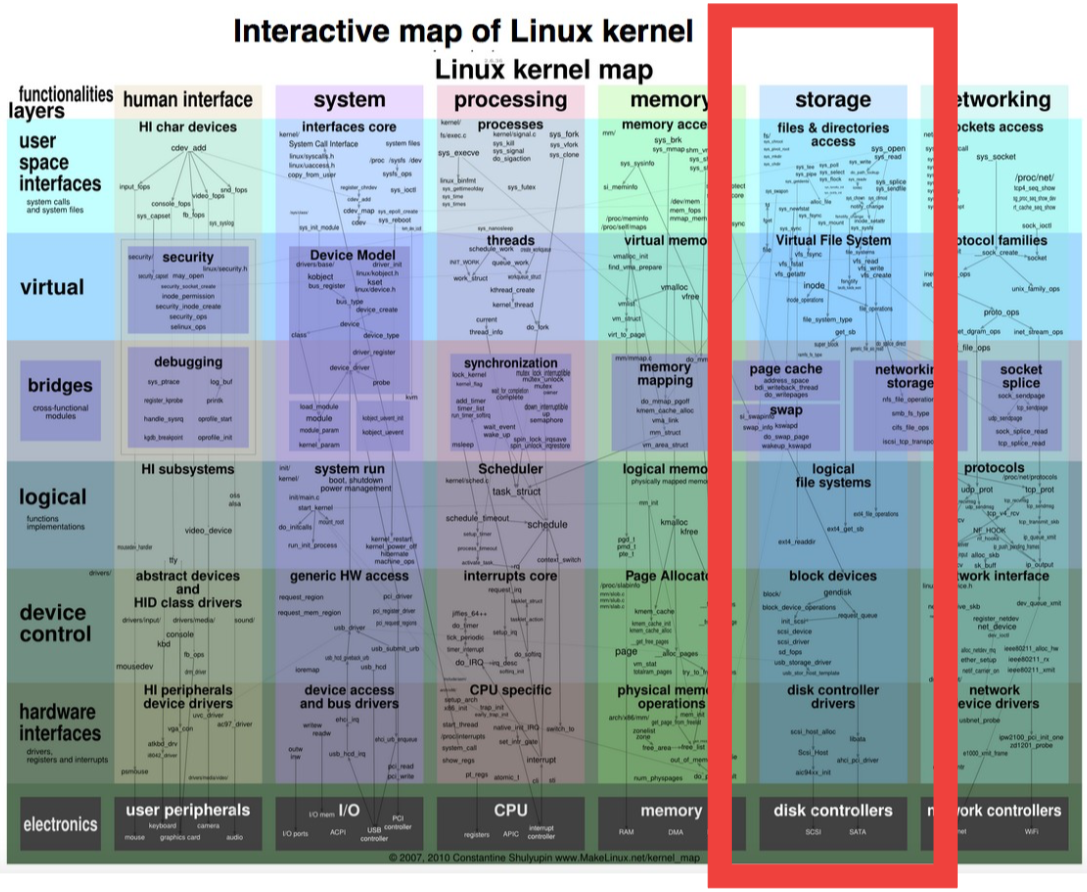

A great resource that helped me to summarize my knowledge about Linux kernel (and about OS kernel in general) was Linux Kernel Map. To do not focus too much on this excellent reference by itself, we can just take a look of the kernel functionalities (the X-axis): HI (human Interfaces), System, Processing, Memory, Storage and Networking. These “functionalities” are pillars of the kernel or main responsibilities if you will. So essentially each kernel is responsible for serving Human Interface devices (to allow us to communicate with the hardware), managing system resources (from software interfaces way down to I/O), do processing (making use of the CPU) and managing: Memory, Storage and Networking.

Because in POSIX everything is a file and also after early days each serious OS is able to serve multiple FileSystems (including pseudo filesystem, that kind of FS that is not backed up by any permanent storage) things are going a little bit more interesting, or complicated if you will…

How we can describe Filesystems and what are differences between them?

If we will go to Linux kernel source code and open filesystem (‘fs’) folder we can see a lot of subdirectories, each of them corresponds to some filesystem implementation.

$ cd ./linux-master/fs

$ ls -d ./ls/*/

./9p/ ./bfs/ ./configfs/ ./ecryptfs/ ./ext4/ ./gfs2/ ./isofs/ ./minix/ ./notify/ ./overlayfs/ ./ramfs/ ./tracefs/

./adfs/ ./btrfs/ ./cramfs/ ./efivarfs/ ./f2fs/ ./hfs/ ./jbd2/ ./nfs/ ./ntfs/ ./proc/ ./reiserfs/ ./ubifs/

./affs/ ./cachefiles/ ./crypto/ ./efs/ ./fat/ ./hfsplus/ ./jffs2/ ./nfs_common/ ./ocfs2/ ./pstore/ ./romfs/ ./udf/

./afs/ ./ceph/ ./debugfs/ ./exofs/ ./freevxfs/ ./hostfs/ ./jfs/ ./nfsd/ ./omfs/ ./qnx4/ ./squashfs/ ./ufs/

./autofs4/ ./cifs/ ./devpts/ ./exportfs/ ./fscache/ ./hpfs/ ./kernfs/ ./nilfs2/ ./openpromfs/ ./qnx6/ ./sysfs/ ./xfs/

./befs/ ./coda/ ./dlm/ ./ext2/ ./fuse/ ./hugetlbfs/ ./lockd/ ./nls/ ./orangefs/ ./quota/ ./sysv/At this moment someone can aks an obvious question: “filesystem is the storage component in the kernel but why do we need so many of them and what is the difference between them?”

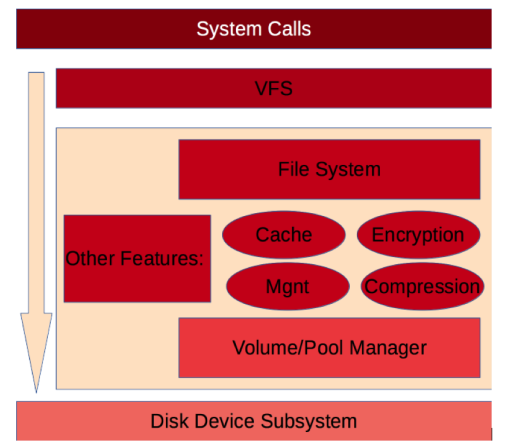

As I pointed out the first difference between is that we can divide them based on the fact that they are permanent (backed by permanent storage like HDD/SDD disk) or temporary (lost content of the file after every reboot). But still we have many permanent FS, so this criterium is not the only one. Next important class of Filesystems can be their design: there pure FS that does not come with own volume manager and more complex that embedded some of the features like device management inside them. But what that exactly mean?

Classical architecture:

Let’s briefly take a look on the classic design of storage stack. Starting from the top we have layer responsible for handling system calls from userspace (application space), no surprise here that is the way how UNIX based Operating Systems are handling any task from a user. Nest we have VFS layer, this layer is abstraction around all possible Filesystems which is independent of any particular implementation. Then we have a particular Filesystem implementation specific code and below it Volume Manager which is a layer that manages target physical devices. At the bottom of the stack, we do have a layer of drivers for devices that we want to use as a storage.

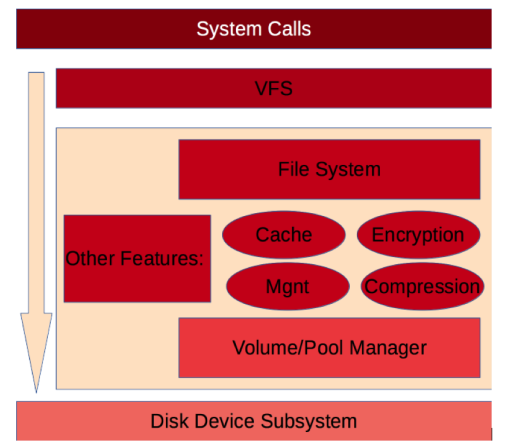

More modern approach, rule devices from FS:

Now we will review, a historically newer approach which came with Sun implementation of ZFS. The idea was to merge the Filesystem layer with Volume Manager. Thanks to this approach some features like snapshots, encryption or compression are also implemented in the common code base which makes them faster, better integrated and more reliable. Not only ZFS uses this approach also younger BTRFS uses such combined architecture.

What all of that mean for the system user?

We covered some theory, necessary to understand the basics concepts. Right now I want to show some difference in managing Classical double components (FS + VM) filesystem like ext4 or xfs and monolithic FS like ZFS or BTRFS. Here I will get my favourite two filesystems: xfs and ZFS and I will show the difference in their management on the Ubuntu machine, also I will point out some interesting features

First step: setup Filesystem.

As a First example, we will setup Filesystem using existing disk device. To do this on filesystem without embedded volume manager we need to separately setup logical volume and then create FS. Of course, you can just create Filesystem straight away on the device itself or physical partition, but this is not most likely the way to follow if you take care of flexibility and future scalability.

# Using Volume Manager to create logical volume

vgcreate lvm_vol /dev/sdb

lvcreate --name rootdg lvm_vol

# Create Filesystem and mount it

mkfs -t xfs /dev/mapper/lvm_vol-rootdg

mount -t xfs /dev/mapper/lvm_vol-rootdg /mnt

:/mnt# df –h

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

/dev/mapper/lvm_vol-rootdg 3.7T 3.8G 3.7T 1% /mnt

:/# vgs

VG #PV #LV #SN Attr VSize VFree

lvm_vol 4 1 0 wz--n- 3.64t 0

:/# lvs

LV VG Attr LSize Pool Origin Data% Meta% Move Log Cpy%Sync Convert

rootdg lvm_vol -wi-ao---- 3.64tWith ZFS because Volume manager is inside FS we do not need to think about devices itself but we operate with pools which are abstraction around physical hardware.

zpool create -f pool /dev/sdb

zfs set mountpoint=/mnt pool

zfs create pool/fs1

:~# zfs list

NAME USED AVAIL REFER MOUNTPOINT

pool 457K 3.84G 291K /mnt

pool/fs1 19K 3.84G 19K /mnt/fs1

:/mnt# df -T

Filesystem Type 1K-blocks Used Available Use% Mounted on

pool zfs 4031104 256 4030848 1% /mnt

pool/fs1 zfs 4030976 128 4030848 1% /mnt/fs1Next step: managing Snapshoots.

Snapshots are important Filesystem feature. By them, we can create a point in time image and hold it for future in case of failure, or just for reference. Implementation of this feature can be Filesystem dependent or handle externally by Volume Manager. XFS does not directly implement this feature inside the code base, while ZFS handle it internally. Let’s take a look at how to create a simple snapshot on ZFS, and then we will compare it with LVM snap shooting under xfs.

:/# cd /mnt/fs1

# Download test ASCII File

wget... - 'alice30.txt' saved [159332/159332]

:/mnt/fs1# zfs snapshot pool/fs1@testsnap1

:/mnt/fs1# zfs list -t snapshot

NAME USED AVAIL REFER MOUNTPOINT

poolik/fs1@testsnap1 28K - 116K -

:/mnt/fs1# mv alice30.txt wonderland.txt

:/mnt/fs1# ls

wonderland.txt

:/mnt/fs1# echo "Hello Alice" >> wonderland.txt

:/mnt/fs1# mount -t zfs pool/fs1@testsnap1 /mnt1

:/mnt/fs1# ls /mnt1/

alice30.txt

:/mnt/fs1# mount | grep fs1

pool/fs1 on /mnt/fs1 type zfs (rw,relatime,xattr,noacl)

pool/fs1@testsnap1 on /mnt1 type zfs (ro,relatime,xattr,noacl)

:/mnt/fs1# diff /mnt1/alice30.txt ./wonderland.txt

3852a3853

> Hello Alice/mnt# lvcreate -L 1M -s -n vol_snap /dev/mapper/lvm_vol-rootdg

Rounding up size to full physical extent 4.00 MiB

Volume group "lvm_vol" has insufficient free space

(0 extents): 1 required.

# Fix the issue

lvdisplay lvm_vol

lvreduce -L 200G /dev/lvm_vol/rootdg

Resize2fs /dev/lvm_vol/rootdg 100G

lvcreate -L 1M -s -n vol_snap /dev/mapper/lvm_vol-rootdg

mount /dev/mapper/lvm_vol-vol_snap-cow /mnt1Here we see something specific to heterogeneous solutions: we should think about space for the snapshot at the beginning of the process, when we created a filesystem, now we run out of space because our FS occupied the whole device. To fix that we need to reduce space for FS, such an issue does not exist with ZFS as VM is integrated and handle space management internally

Extra: transparent compression:

One really useful feature that came with integrated volume manager file systems is transparent compression. Thanks to compression we can reduce the size of some of the files that we store in the FS. I don’t want to go to deep details of compression itself but files that are likely to benefit from this feature is especially text files, source code, some of the binary files or bitmaps and things that aren’t best fit for compression are: Images in compressed formats like jpg (because they already became compressed) or encrypted files.

Lets see how easly is to setup compression (we will use lz4 algorithm).

zfs set competssion=lz4 pool

zfs set compression=on pool

zfs get compressratio /mnt

NAME PROPERTY VALUE SOURCE

poolik compressratio 1.00x -

# Download test ASCII File

wget http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11/11-0.txt

for i in `seq 1 1000`; do cat alice >> alice; done

ls –lahtri alice

13 -rw-r--r-- 1 u u 3.0M Apr 25 00:51 alice

zfs get used,logicalused poolik

NAME PROPERTY VALUE SOURCE

poolik used 435K -

poolik logicalused 3.40M -

zfs get compressratio /mnt

NAME PROPERTY VALUE SOURCE

poolik compressratio 10.77x -So as we can see we were able to save 10 times of our storage medium! It looks incredible but in reality, we used the trick by storing de facto same content copied many times. In reality, the ratio will depend on the files that you store. In example my FreeNAS based home storage server where I store photos compression ratio is 1.01

Future Reading:

In this article, I touch basics about Filesystems and Volume Manager. This material is the tip of the iceberg for everyone who wants to deepen his knowledge of FS. Either from the implementation or administration point of view. As an extra exercise curious reader: can try to find what is the COW design of FS which Filesystems are COW and aren’t. Then try to figure out how the design effect features that we discussed.

Additional resources:

Linux kernel Map: http://www.makelinux.net/kernel_map/ Test ASCI Book “Alice in Wonderland”: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11/11-0.txt